In 2001 The Orphanage was still a brand-new company, and I was not yet a professional director. The project that changed that was a music video for Cher’s A Song For The Lonely, which Cher had dedicated “to the courageous people of New York especially the fire fighters, the police, Mayor Giuliani, Governor Pataki and my friend Liz.”

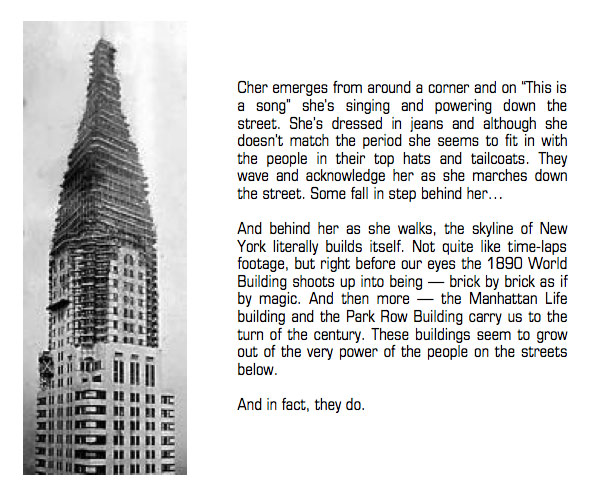

A huge architecture buff with fond memories of a recent Manhattan film shoot in my mind, I pitched Warner Records an idea for a Cher-guided tour through New York’s proud history, exemplified by a multiple reverse-timelapses of some of the great buildings of the city rising up before our eyes. Here’s a page from my treatment:

I got word that the job had awarded and that Cher would be calling me on my cell phone. Her enthusiasm for the concept apparently steamrollered any trepidation Warner might have had about assigning this video to a first-time director.

I was terrified of the entire thing, but when Cher called, she immediately disarmed me. “So what are we supposed to be talking about?”

We shot in December, in New York. We got special permission from the Mayor’s office for live audio playback in the streets of Manhattan, a practice that had recently been outlawed. I hadn’t even met her yet and I was already experiencing how much the city of New York loved Cher.

Photo by John Benson

Cinematographer Rolf Kestermann and I decided to shoot on the brand-new-at-the-time Sony F900. This was in part due to the rapid post schedule and large number of visual effects, but it also facilitated a DV Rebel schedule hack that I had devised with my producer Scott Kaplan. We shot on a Thursday and Friday, and our camera kit wasn’t due back at the rental house until Monday morning. On Saturday, he and I took the F900 and a rented convertible around Manhattan and I shot the B-roll that became VFX plates for some of the signature effects, such as the Flatiron and Citicorp building shots.

One of the best pieces of advice I received was to schedule the shoot so that the very first thing up was complete coverage of the song with Cher looking her absolute best. So we scheduled the “black void” shot for early Thursday morning. This, along with the greenscreen stairs, we would shoot in Brooklyn, and then move to Manhattan for the rooftop shoot.

The black void shot was a huge success, but it almost didn’t happen. The sun wasn’t even up yet and we got word that Cher’s makeup artist, the famous and gifted Kevin Aucoin, was nowhere to be found. Of course much later we would sadly learn that this had been due to his struggling with a terminal illness, but at the time all I could think was that my directorial debut was about to be cancelled before it even began.

Then word came back from Cher’s trailer that she was going to proceed with the shoot—and do her own makeup. She was 55 at the time, and she was about to get in front of the cameras without the aid of her star makeup artist. That was when I realized how committed she was to the project. When she was almost done, I was allowed into her trailer to say hello for the first time that day. She looked stunningly beautiful.

Between takes of the Technocrane shots of her running up the greenscreen stairs, Cher didn’t return to her trailer or even to her chair. She jogged in place near the stairs to keep her energy level up. As I explained the effects that we’d be adding in post, I stopped myself, realizing that this Academy Award-winning actress and accomplished director needed no coaching from me. “You’ve done this before,” I said. “Yeah, but you haven’t,” was her reply. She was onto me. She smiled and put her hand on my arm. I’d walked over to comfort my star and she had wound up comforting me.

That was a pattern that would continue. On day two of our shoot, on the cobblestone streets of Manhattan’s Meat Packing district, I offhandedly called out to my first AD that the extras needed to walk faster in the next take (weirdly there’s sort of a rule that director’s shouldn’t talk directly to background talent—something about it meaning that they are no longer background). As we reset back to the end of the block for another Steadicam take, Cher took my arm and said, “Babe, if you call them ‘extras,’ they’ll act like extras. But if you call them ‘actors,’ they’ll give you their best.”

At least, I think that’s more or less what she said. I had a hard time concentrating after Cher called me “babe.” If there’s one human on the planet who owns that word, it’s her.

We were shooting on public streets with a large crew and full street closures, but we had some challenges dressing our little corner of New York to the appropriate periods. To cover that, we smoked up our streets with big, loud smoke machines. The events of 9/11 were still a fresh and painful memory for the city though, and complaints about our smoke started coming in. The police officer manning the intersection gave word that we’d have to shut down our atmospheric effects, but I still had one more shot that I desperately needed.

My AD leapt into action, borrowing “first team” (that’s Cher) and the script supervisor’s camera and walking over to the cop. An autographed polaroid later, we were shooting one last smoked-up street shot. Again, the power of Cher. On her walk back a guy yelled out his third-story window: “Yo, Cher!” In the thickest New York accent I’d ever heard. Without skipping a beat, she yelled back: “Yo!”

All of this, by the way, in the most brutal December cold that I’d ever experienced in New York. Look at the parka I’m wearing in these photos—It’s designed for summiting Everest. Meanwhile, Cher was strutting up and down the street in skinny jeans, heels, and a thin shirt under a light jacket.

Photo by John Benson

Despite the cold, the street shots went incredibly smoothly and I’m still amazed that we got all the coverage that we did in that one short day. But the rooftop shoot the previous day was another matter. It seemed to take forever to move the company from Brooklyn to midtown Manhattan, and when we got up to the roof, the weather turned on us. Our gorgeous view of the Empire State Building was blocked by dense fog that rapidly became a light but persistent rain. Nevertheless, Cher climbed right up onto the roof—part of which was only accessible by a rickety ladder—and sang her heart out. There are shots where she’s standing in heels a foot away from a thirty-story drop, with only me and her bodyguard holding her feet for safety.

Like every first-time director, I planned a 360-degree dolly shot. I’m not sure which is a more popular bad idea for first-timers, this or the powers-of-ten shot. 360-degree dollies are almost never as interesting for the audience as they seem like they will be to a new director, and they are incredibly challenging to pull off. Imagine lighting a movie star on a giant rooftop, trying to hide the lighting gear from a camera that will see everything, and then asking the entire crew to leave so you can shoot. Including Cher’s vanities team. Guess what happened. The shot wasn’t that great, but worse still, without hair and makeup being allowed their “last looks,” our star didn’t look her best, and we wound up leaving most of the shots out. Although I must say that it was fun crouching at Cher’s feet with my clamshell monitor while the Steadicam rocketed around us on that roof.

I’m more proud that I survived the process of making this video than I am of the job I did as a director. It was my first directing job and my last music video—I wound up being a lot better at commercials. But I’ll never forget the experience and the numerous lessons I learned on this project, and I’m honored to have been a part of Cher’s tribute.

Scott Stewart, Jon Rothbart, Me, Scott Kaplan, Cher, John Benson