I once was asked to describe how I think about photography. In response, I used a stick to draw a Venn diagram in the dirt. I labeled the three zones Fact, Moment, and Light.

You can characterize any photo, and any opportunity for a photo, using this model. It won’t surprise you to learn that I believe the best photos occupy the intersection of all three zones — but first, let’s look at each zone individually.

Most of us live our entire photographic lives in the Fact zone. We take photos of people, events, and places that are important to us. It’s Timmy’s Birthday. We Went To Paris. Cousin Sally Got Married. These are facts, and most people take photos to document facts. They are not seeking to capture emotional truth, they are simply trying to preserve their memories of what happened.

This is why most people are disappointed with most of their photos. They want to preserve memories, but what they really mean by that is that they’d like to create an image that makes them feel like they did when they were there. Crappy photos rarely fail to document the facts, but they inevitably fail to capture emotion — because they ignore the other two zones of the Venn diagram.

Here’s a photo that I made years ago when new gantry cranes were being moved into the Port of Oakland. The mere fact that a boat is carrying the world’s four tallest cranes under the Bay Bridge with only 18 inches of clearance makes this photo interesting — but it ends there. This photo totally fails to capture how I felt seeing this stunning event in person. The Fact Zone is the domain of the snapshot. At its worst, it’s the picture you take with your phone to help you remember what floor you’re parked on.

After being repeatedly disappointed with our factual, emotionally-bereft photos, we eventually figure out what the next zone has to offer our photos. We tap into the Moment zone when we realize that it actually matters when we release the shutter. That Timmy’s anticipation of blowing out his candles might be a more vivid moment than his exhalation. That out of a dozen photos of Sally reciting her wedding vows, there’s only one that brings a tear to your eye. We often start by noticing that some of our Fact Zone photos have accidentally encroached into the Moment Zone—we’ve captured not only the facts, but the perfect expression, the ideal pose, the most dynamic framing.

In this photo, I got lucky with the moment. I had framed up a nothing-but-the-facts shot of Flaminio Vacca’s Lion in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a man walking into my frame — just the foreground element my boring shot needed. My Fact shot was about to graduate to an F+M, if an unimpressive one. I released the shutter as he entered the shot, and only later realized that he had been looking right at me, and that he was a dead ringer for the lion.

You’ll notice that there’s no zone for composition. Good composition is, of course, a necessity for any great photo. But good composition is, in my opinion, attainable in any situation, whether you have all three zones in effect or only one. There are such things as unique opportunities for great composition — file those under the Moment Zone.

When we discover the importance of the Moment Zone, we begin to despise our point-and-shoot cameras for how painfully slow they are to respond to our fevered finger-pressing. When we graduate from a sluggish pocket camera to a responsive SLR, we awaken a love affair with the Moment Zone. We now aspire to the Fact + Moment shot, where we’ve got both the subject matter and the timing nailed. With this aspiration in our heads as we snap away, our photos are pretty good.

And then we notice that some are accidentally coming out great. We see that some of our photos actually capture the emotion we felt when we were there. And not just for us, but for others as well — a stranger looking at this photo would feel exactly as you did when you made it, or as your subject did. This is the apotheosis of communicating with photography, and it happens when your shot of the right fact, at the right moment, also has beautiful light.

Photos are nothing but light — it’s literally all they are made of. Timmy’s birthday and Sally’s wedding are reduced to nothing but photons before they become photographs. So getting the light right is more meaningful to a photo than anything else. Yet this is often the last zone we discover. It’s also the hardest zone to control, but not nearly as hard as most people think. Turn off your flash. Ask your subjects to move. Guide them with your body language. But most of all, notice when the light is doing something amazing, and then wait for the other two zones to happen on their own. What you’ll discover is that any photo in the Light Zone is going to be pretty dang good. All the better if you can get an Fact + Light shot, or a Moment + Light shot.

Here’s a Fact + Light shot from my recent trip to Italy. This Duomo in Siena is interesting enough on its own, but it was the light that made me reach for my camera.

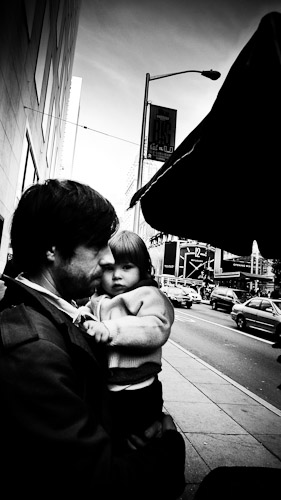

Here’s a Moment + Light shot I made in San Francisco’s Union Square. I like the way this image looks, but the photo doesn’t have a reason for being beyond looking pretty—I don’t know these people, and this photo isn’t helping me learn anything about them. Moment + Light with no Fact means a pretty, but empty photo.

Here is a FML shot I made last year near my home in Emeryville. I was returning from an unsatisfying photowalk when I bumped into a group of guys about to hitch a ride on a freight train to attend the Democratic National Convention in Colorado. They were pumped up about their trip, and I offered to commemorate it for them with a photo. I gently guided them toward the best light and made a couple dozen exposures. Of them, this one makes me the happiest. It’s full of fun facts (is that a joint in his hand? Is it so important that he keep it lit that he’s tied a lighter to his wrist? What do those tattoos say? Caution tape?), it’s the right moment, and the golden-hour light is glorious.

I suppose I could have made this shot at 12 noon, or on an overcast day—but the truth is, that light is the only reason I was out there with my camera in the first place, and the only reason I stopped those guys and asked where they were going. After years of working my way through the zones from Fact to Moment to Light, I now start at the end and work back. Light is what gets my camera out of the bag. Moments I know I can find if I’m patient. And Facts matter to me least of all now. The mere fact of being at the Eiffel Tower is not enough reason to make a photo, but the challenge of finding the light and the moment that help capture exactly how I feel at the Eiffel Tower is what makes photography endlessly rewarding to me.

Update

on 2013-07-16 22:45 by Stu

If you enjoyed this post, you might also want to take a look at the Prolost Presets for Lightroom.

Update

on 2009-04-14 01:22 by Stu

By the way, I'm not a professional photographer, or even a very good one—so you can take this all for what it's worth to you. I've described my personal progression toward being happier and happier with my own photos. I have the great luxury of requiring nothing more from my photography than that.

You can see my favorite flickr photos here. You can see more photos from my Italy trip here. You can see the other shots of the Colorado-bound gentlemen here. My 12 "most interesting" (according to flickr) shots are here.